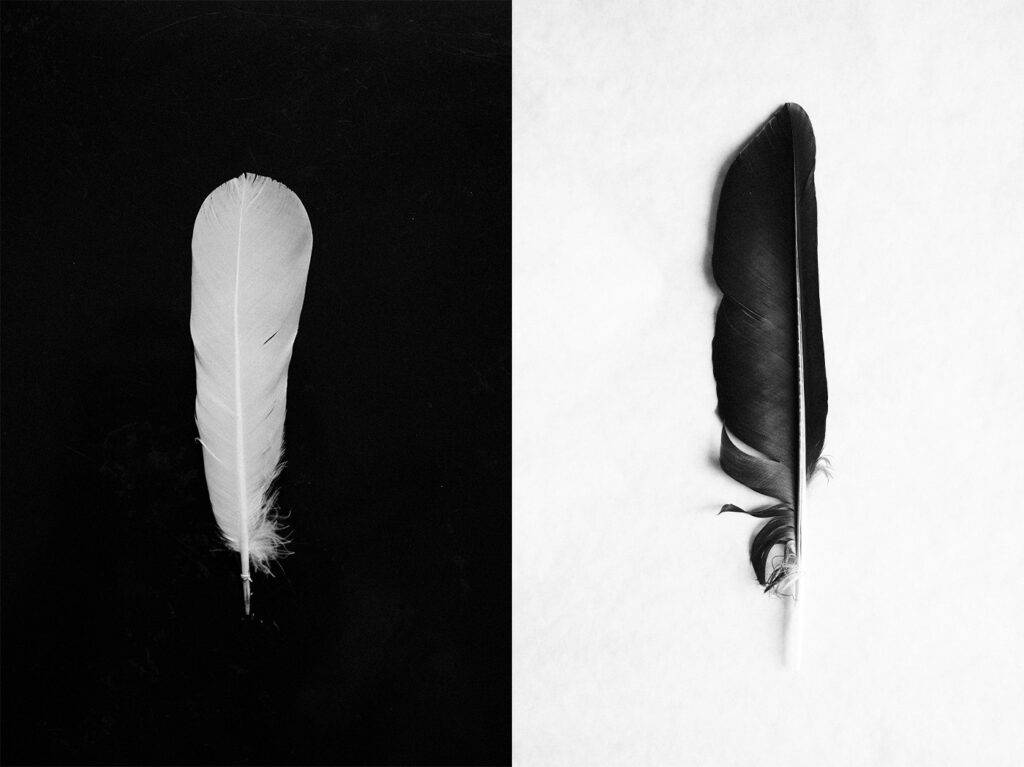

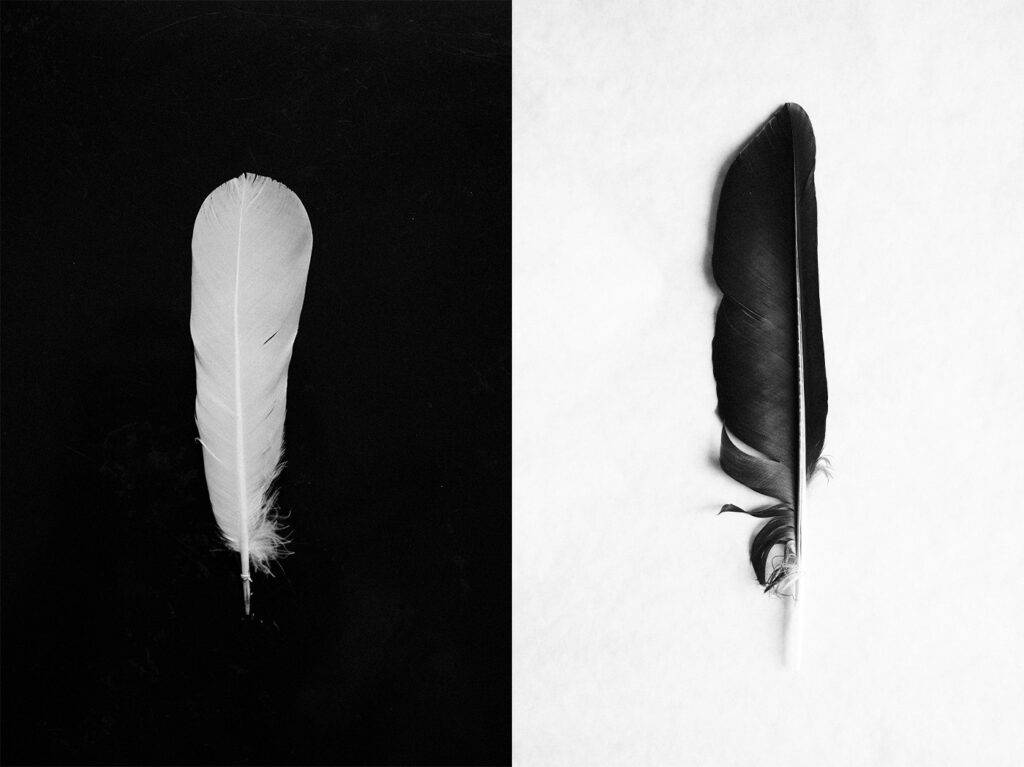

As Ukraine enters the second year of the Russian invasion, photographer Andrii Kasianchuk still finds inspiration for his work. While experiences of the war are varied and personal for all Ukrainians, there is a collective agony that brings them all together and propels them onward. As Andrii sees it, “the nation and the country have found themselves at the crossroads of two worlds: life and death, light and darkness, freedom and enslavement.” From these crossroads, Andrii developed his project Inpu, a “warzine” that provides a discrete glimpse into one of those experiences.

Photos by by Andrii Kasyanchuk

Words and interview by Michaela Doyle

After fleeing the center of Kyiv on the second day of the invasion, Andrii and his family spent two months in a small village in the Kyiv region. When the Russian troops left Kyiv, he returned with his wife to the capital to try to get back to some version of “normal”. But this is never really possible in the midst of a war. As he explains, “the danger of rocket attacks remains to this day. They occur regularly, but we need to live on, develop and help the army liberate the country.”

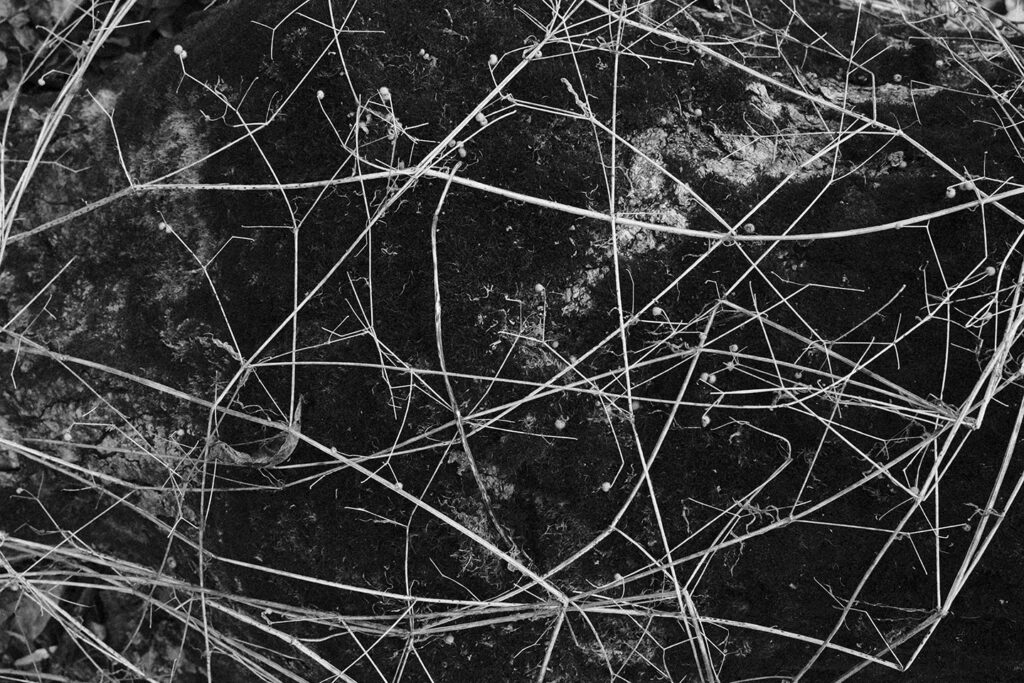

During the two months outside Kyiv, Andrii began to document his life with his family far from the front lines. As he looked back on what he had captured, he noticed the symbolism of his inner experience coming out in his photographs. The resulting work features windswept expanses, bare winter trees, familiar interiors and an assortment of animals—wild, tame, alive and dead—but few people. While he was with his family, he spent a lot of time alone, beginning to process the war. His project reflects that experience: “It’s like one long meditation, like being in two dimensions at the same time.”

The title of the warzine comes from the Egyptian name of the deity commonly known in its Greek rendering as “Anubis”. Inpu, sometimes written as Anpu, is the ancient Egyptian god of funeral rites, represented as a man with the head of a black jackal. Inpu served as the guide to the underworld, preparing the bodies of the dead for burial and accompanying their souls into the afterlife. In this way, as Andrii explains in his warzine, “the title of the series seems to hint at loneliness, personal choice and the path to be overcome”.

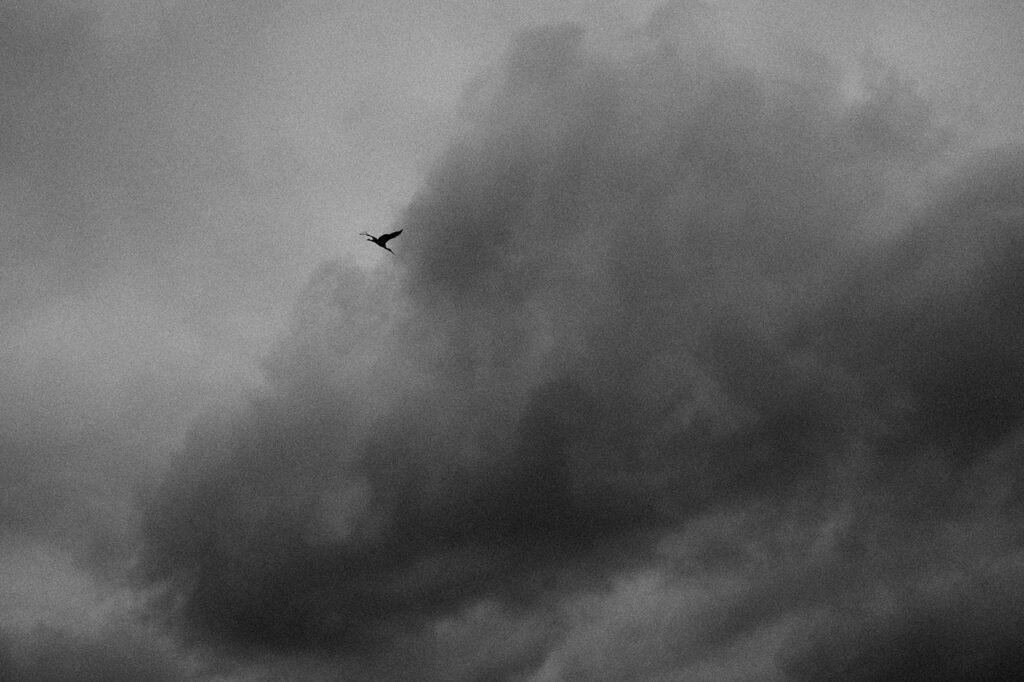

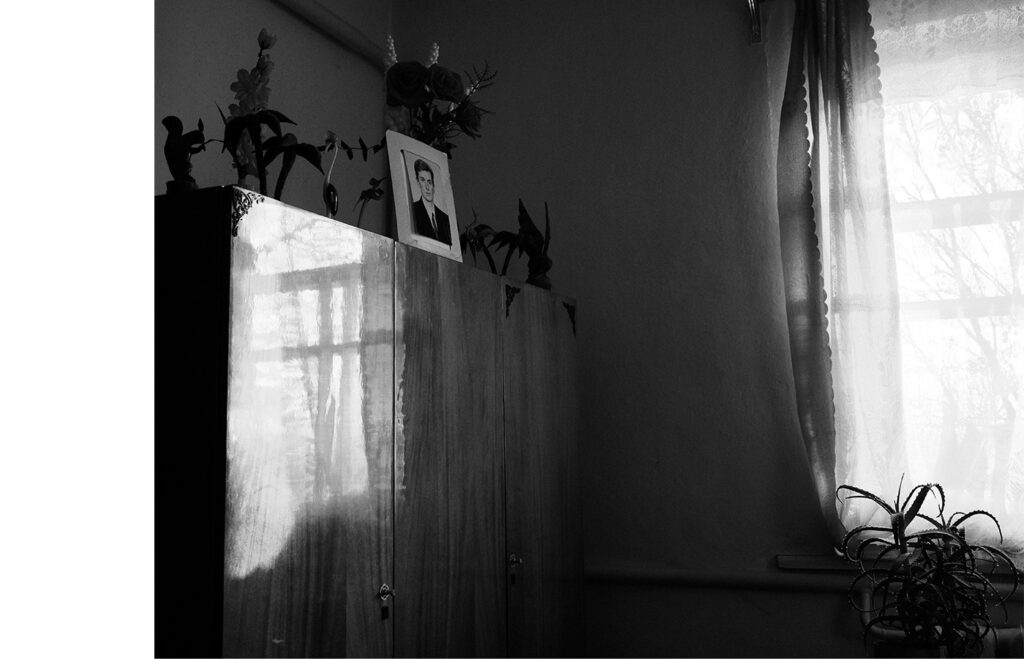

The photos have diverse subjects but are tied together in their essence and mood. While there is an overarching stillness to the collection, there is also, as Andrii puts it, “a feeling of movement and oscillation between dusk and dawn.” He continues, “In one image, the calm whiteness of a dead animal’s bones contrasts with the process of knitting the ‘threads of life’ in another.” In one of the interior images, a photo of a young man sits high on an armoire in a tidy, light-filled room; in the next, another man in a small painting looks directly at the viewer from his place on the wall, proposing a conversation between generations and a contrast between life and death. We also see horses up close and fenced in, juxtaposed with a stork flying gracefully far overhead.

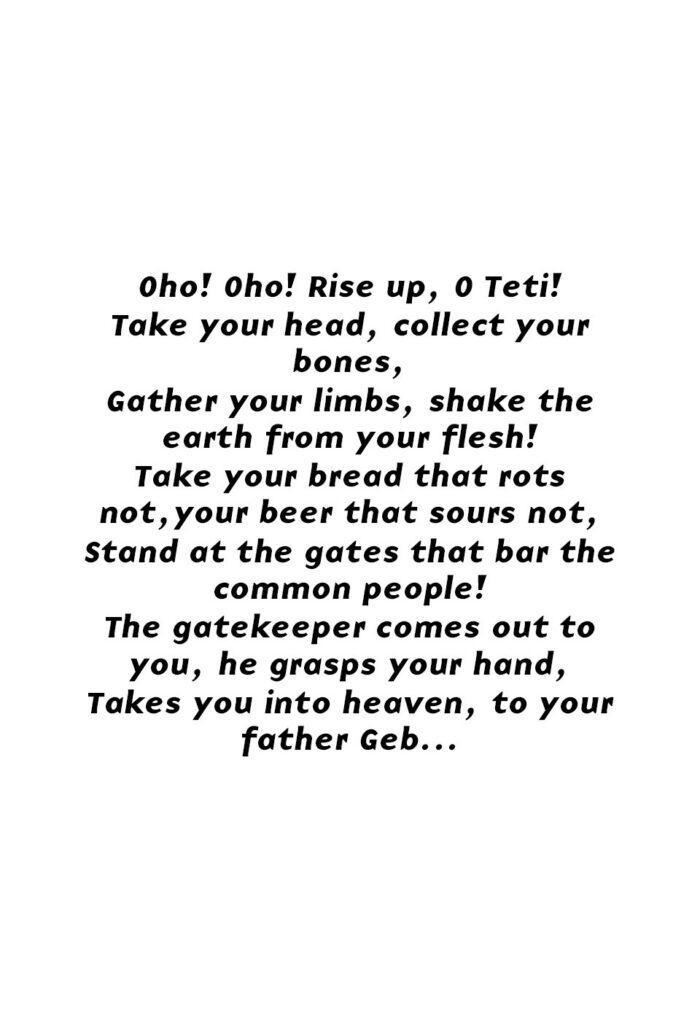

Andrii’s warzine also features quotes from the “Book of the Dead”, a collection of ancient Egyptian texts believed to aid the deceased in moving through the afterlife. The texts, the title of which directly translates as “The Chapters (or Book) of Going (or Coming) Forth by Day”, outlines a lengthy series of challenges the dead must go through to ultimately enter the realm of the gods. As Andrii explains, “the contrast between the brutality of war and the peaceful afterlife described in the Book of the Dead was stark and poignant.” This duality that appears in and between Andrii’s photographs is similarly present throughout the daily lives of Ukrainians everywhere. The war continues to wage, and still: winter becomes spring; horses graze and gallop and storks drop their feathers; people work and sleep and knit and walk.

Below are excerpts from ZOOT’s conversation with Andrii.

How did you choose the excerpts for the poems in the Warzine? Why the Book of the Dead?

The Book of the Dead, an ancient Egyptian text, is a collection of incantations, hymns and prayers designed to guide the deceased through the afterlife and ensure their well-being in the afterlife. It struck me that this text, written thousands of years ago, still applies in many ways to the situation I am experiencing in my homeland: witnessing death, destruction and chaos all around me.

The war in Ukraine is characterized by intense violence, displacement and human casualties. The Book of the Dead, for its part, was a text that sought to comfort the dead and give them peace. This testifies to the belief of the ancient Egyptians in the afterlife and the desire to help their loved ones reach that world. The contrast between the brutality of war and the peaceful afterlife described in The Book of the Dead was stark and poignant, and it inspired me to include excerpts from it in my zine.

I chose certain verses from The Book of the Dead that I felt reflected the themes of death, struggle and hope. These poems talked about the journey of the deceased person, the obstacles they faced and the belief in a peaceful afterlife. This sense of hope resonated deeply with my feelings when the entire country found itself in a situation of maximum proximity to death and at the same time an unprecedented belief in resilience and victory.

Horses and storks feature prominently in your photgraphs. What is it about them that you felt drawn to?

Storks and horses have great symbolism in many European cultures. In Ukraine, many folk proverbs and beliefs are associated with these animals. They symbolize purity, resurrection and the birth of life. Since ancient times, horses have been used as carriers of both the living and the souls of the dead. In Ukraine, people believe that if a stork settles near your house, it means that it is under the protection of higher forces and nothing bad will happen to its inhabitants.

One day, at the beginning of March, returning from the forest with my dad, we saw a large flock of birds circling above our house, which later landed near us. It was very symbolic and touching.

In the few images taken inside the house, there are framed and unframed photos and portraits featured. Is there a significance to these? Who are the people in your photos and portraits?

The two photos in the room have a strong contrast between them. One picture features my dad in his youth while the other depicts my great-grandfather who lost his life in World War II. Although I initially did not put much thought into these photos, the contrast between life and death was the focal point. These photos are in the same room and almost opposite each other, which is what prompted me to pay attention to them.

The other photos tell different stories as well. One photo captures my wife engaged in knitting, a leisure activity that helps her relax and distract from the events happening outside. In the picture, she is knitting a decorative napkin, a common household item in Ukrainian homes. Another photo shows my grandmother in the dark, trying to find the source of a loud noise that turned out to be a fighter jet flying over our village.

You describe the title, “Inpu”, as hinting at “loneliness, personal choice and the path to be overcome”. Can you speak a bit more about this? How did this tie to those first two months with your family at the beginning of the war?

Yes, in these photos I tried to convey my feelings and emotions at the moment when the whole country faced an important choice: fight or surrender. This question concerned absolutely every citizen.

On the eve of a full-scale invasion, there was an indescribable metallic taste of war in the air. After the invasion, this taste was replaced by another, the taste of freedom and struggle. That’s exactly how I felt. I saw and understood that in the first hours Ukrainians made their choice and understood that the path we will choose will be extremely difficult.

With such thoughts and mood, I spent the first two months wandering around the village where I lived, trying to find solace in photography. Only later did I realize how aptly I had managed to convey the depressing mood of those days.

It’s interesting you chose to use the original Egyptian version (Inpu) of the more common Greek rendering “Anubis”. Can you tell us more about your choice of title?

During my research into the afterlife of Egypt, I became interested in writing the name of a deity in Egyptian hieroglyphs. I thought it would be more appropriate to use his original name. I originally planned to use only hieroglyphs in the title of the photo series, but realized that it would be confusing and difficult to spell and pronounce. So I chose a simpler spelling of his name.

Is there something you want to communicate to Ukrainians in this series? Or something you want the global community to understand about the Ukrainian experience, as illustrated through your series?

This series was primarily to document my experience and stay in my homeland during the war. I didn’t know how this series would end or if I would be able to finish it. Fortunately, and thanks to the resilience of my people and the Armed Forces of Ukraine, I am able to write this now.

Perhaps this series has remained like that, a story.

I believe that for Ukrainians today, this series is another reminder of the events of the first days, another unhealed wound that is pressing on. Most likely, after some time, after the victory, it is worth returning to these photos and feeling these emotions and experiences again. Remember the price we paid.

These photos will help viewers from other countries to be emotionally closer to our tragedy and our struggle. They will show how much closer death can be than we think. To remind what sacrifices people are capable of making for the sake of freedom.

Where does your inspiration come from?

As trite as it sounds, anything can inspire me. The most important task is to remember or write down what comes to mind. For inspiration, I like to look at other photographers’ photos, feature films or books. A kind of meditation for me is a long trip or time spent alone in nature.

How has the war impacted your creative process? Has your creative process changed during this time?

Of course, for most people, war is an indescribable stress. Although the human psyche is able to adapt to the environment, it happens in different periods of time for everyone. I couldn’t focus on creativity for a very long time. For a long time I did not publish my photos, it seemed to me not quite ethical. It’s only now that I’m starting to get back into the creative direction and planning shoots, thinking about future projects, etc. Compared to 2021, last year 2022 I took a lot less pictures. This is also the case with many photographers I know.

Is there a particular artist or art movement you identify with?

There is an extremely interesting phenomenon in the history of Ukrainian photography. This is the Kharkiv School of Photography. During the time when Ukraine was under the rule of the USSR, its representatives created completely new bold, provocative images that did not fit into the general concept of photography of the Soviet era. It was a closed photo club, whose bright representatives are Borys Mykhaylov, Yevhen Pavlov, Roman Pyatkovka, Oleg Malyovany.

I really like their creativity and often look to their work for inspiration. But personally, I cannot consider myself a representative or imitator of any particular artistic direction. I like to feel freedom in this sense, to look for something new and at the same time turn to already known practices. I like to experiment with genres, form, instruments. In my opinion, this is development.

Can you tell us a bit more about your experience of the early days of the war? Where were you when it started? What are the most significant ways in which it has affected your daily life and the lives of your family and friends?

I used to wonder how my grandfather could remember so much from his WWII childhood. Now I understand that the memories of this war in Ukraine will forever remain in my memory, down to the smallest details.

On February 24, around 5 in the morning, we were woken up by a powerful explosion near our apartment in Kyiv, and a few minutes later, a jet plane flew overhead. The news reported that Russia had invaded Ukraine. Shops and pharmacies were closed, and there were traffic jams on the roads. We spent the first day at home, constantly reading the news and listening to the sounds of explosions that reached us.The next day, the shelling of the city intensified, and the explosions came closer and closer to our house. We sought refuge in a crowded subway. After a few hours we decided to try to leave the city while we still could, as reports were spreading that the city would soon be surrounded and all the roads would be blocked. We left the city on the last bus to my grandmother’s village, which is 130 km from the capital. Due to traffic jams, the road that usually takes about 2 hours then took 8 hours. Later, my parents also came from another city. For two months, we lived under constant threat, with jet planes, military helicopters and Russian missiles flying over us every day. One morning I watched in horror as two Russian cruise missiles flew over our house with a deafening roar just 20 meters away.

The war touched every Ukrainian, and my family is no exception. Although there are no soldiers in my family, and my parents and wife are teachers, many of my friends, colleagues and acquaintances are now fighting in the east of Ukraine. Unfortunately, some have already lost their lives.

Has there been a moment over the past year that you felt most proud to be a Ukrainian?

It happens every day. From the first day of the invasion, Ukrainians rallied and united so strongly that it can only cause pride. Of course, in those moments when our soldiers return from captivity to their native land, when troops liberate captured territories, when even children sell their own toys, collecting aid for the military, and there are many such examples, all this causes pride and tears in the eyes.

What do you think the international artistic community can do to help Ukrainian people? How can we all help?

First of all, it is support in all its manifestations. This has been happening since the first days of the war, we appreciate it and are infinitely grateful to all the countries and people who responded and came to help in this difficult time. But we should not forget, the war is still going on, people are dying and it is necessary to continue to support and work for the victory of the entire civilized world over the “prison of nations”.

What do you imagine your life will be like when the war is over? What’s the first thing you will do then?

After the victory, there will be a lot of work to rebuild the country. This is also a very difficult path, but we will overcome it too.

First of all, I will definitely meet with friends and celebrate all night until morning.

All photos were taken by Andrii Kasanchuk in the vicinity of the village of Denykhivka, south Kyiv region, in the period from 26 February—29 April 2022.

Layout support from Ana Sousa Costa.